What Should Our Kids Know About Label Reading?

Recently my teenage daughter was asked to design food packaging for a healthy food product as part of her homework. It got me thinking that with so much of our diet made up of food in packaging, and looking to the future where this appears to be more often the case, we do really need to ensure that our children can discern real, health-giving food and ingredients from the kinds of food that may cause them health problems further down the line. I’ve created this piece that follows to help you explain what food labelling is and how our children can use it to their advantage. This is how I explained it to my daughter.

Why do we need food labels?

Food labels exist to guide us when making food choices. They show what food groups each item contains and in what quantities, how fresh it is and how to prepare it. The labels are also there to help us eat more healthily. What this means is that ideally you’d be able to use the labels on food packaging to work out which foods will help you to achieve the overall goals of:

• eating less ADDED sugar

• eating at least five portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables every day

• including some protein-rich foods such as meat, fish, pulses and dairy foods in each meal

Ingredients Labels:

In the UK any food or drink that has 2 or more ingredients must have a food label listing the ingredients in weight order. The ingredients at the top of the list are therefore found in that product in the greatest amounts. If you are buying tomato soup for example you’d expect the first ingredient to be tomatoes. However, also watch out for one of the most common ‘tricks’ on the part of food manufacturers which is adding sugar to ‘savoury’ products. Watch out for added sugar in places you wouldn’t expect it, such as breads, sauces, dressings and soups.

Nutrition labels

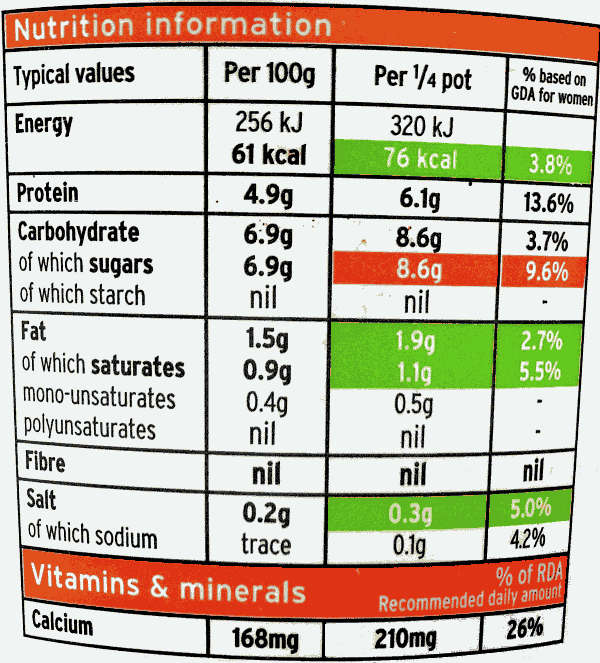

As well as ingredients labels there are also nutrition labels to become familiar with. These are listed in terms of macronutrients (i.e. carbohydrate, protein, fat) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals).

The UK Government provides some guidelines so in theory you can work out which foods are Low, Medium or High in Fat, Saturated Fat, Sugars and Salt.

| (All measures per 100g) | Low | Medium | High |

| Fat | 3g or less | >3g – ≤17.5g | More than 17.5g or >21g/portion |

| Saturated fat | 1.5g or less | >1.5g – ≤5g | More than 5g or >6g/portion |

| Sugars | 5g or less | >5g – ≤22.5g | More than 22.5g or >27g/portion |

| Salt | 0.3g or less | >0.3g – ≤1.5g | More than 1.5g or >1.8g/portion |

What this doesn’t allow for is the fact that some very healthy, natural and real foods are high in fats naturally i.e. nuts, avocado, olive oil. Don’t be discouraged from eating these foods as they are real foods. If all food consumed was real then these fats would be consumed only until you’d eaten enough and not beyond. Too much fat is consumed when it is combined with sugars, salts and a particular mouth-feel in the way manufacturers of processed foods have identified successfully as the “bliss point“.

Macronutrients are most commonly listed on the food packaging but less so micronutrients. You tend to find micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) listed on the packaging of fortified products such as cereals and breads. However, that doesn’t mean they don’t exist in other foods too. They’re plentiful in many natural foods that don’t require a food label such as a pineapple.

In one portion of pineapple (165g) there is:

95.71IU Vitamin A

78.9mg Vitamin C

0.1mg Thiamine

0.2mg Vitamin B6

There just won’t be a label to tell you how much of each micronutrient is in such foods. Eating natural foods with no food labels is a good thing to do. A good quote to remember when making food choices is “don’t eat anything incapable of rotting” (Michael Pollan).

Nutrition and Health Claims

Be aware of nutrition and health claims on food. These statements are designed to make the product seem more appealing by making it seem more nutritious and/or healthier. If you see “light” or “lite” on a product then the product must be at least 30% lower than the standard product in one of its values such as calories or fat. That really doesn’t mean it is any healthier though. What this claim doesn’t allow for is what may have been then added to the product to make it more palatable. Often when fat is removed sugars and therefore calories actually go up. If you check nutrition labels on comparable foods you may be surprised at how little difference there is between foods that carry health and nutrition claims and those that don’t.

If you see “low fat” on a food then it contains no more than 3g of fat per 100g or 1.5g of fat per 100ml of product. Does “low fat” mean healthier? In short, no! Some foods are just naturally low in fat and some are not. Nuts are not a low fat product but they are not an unhealthy food. Whereas some sweets have no fat in them but they also contain nothing of nutritional value to anyone, let alone a growing human.

How about “no added sugar” or “unsweetened”? This doesn’t necessarily mean that the food contains no sugar. Where you see either of these labels sadly you will need to look at the ingredients label to see what types of sweetener may have been added instead. Also no added sugar doesn’t mean the food or drink doesn’t taste sweet AND it can still contain sugar, just natural sugars. Think about fruit juice which contains no added sugar but which provides a hit of sugar.

When you see nutrition or health claims on food packaging you have to ask yourself whether they actually are more nutritious or healthier or not.

Sugar

Check ‘Carbohydrates – of which sugars’ and be wary of anything with over 22.5g sugar per 100g of product or over 27g sugar per portion as these are high in sugars. The figures for sugars on traffic lights are for total sugars so they don’t tell you how much of the sugar is added (free sugars) and how much of the sugar is naturally present. For example a plain low fat natural yogurt will contain no free sugars, but will contain naturally occurring lactose (the sugar found in milk). A fruit flavoured yogurt would contain some added sugar, which would be classed as free sugars. Sugars which occur naturally within the product will not be listed as an ingredient. Check the ingredients list – if syrup, invert syrup, cane sugar or anything ending in ‘ose’ such as fructose, sucrose or glucose is within the first three ingredients, this suggests the food contains more added sugar.

A note on Reference Intake (RI) values:

This a new way of getting an indication of the nutrient value of the foods you are trying to choose between. It also helps you compare two similar products. Unless the label says otherwise, RI values are based on an average-sized woman doing an average amount of physical activity. The reason this is the case is to reduce the risk of people with lower energy requirements eating too much, as well as to provide clear and consistent information on labels. Note that children’s requirements may be more or less than this depending on age, sex, level of activity and also how developed you are.

As part of a healthy balanced diet, a female adult’s reference intakes (“RIs”) for a day are:

Energy: 8,400 kJ/2,000kcal

Total fat: 70g

Saturates: 20g

Carbohydrate: 260g

Total sugars: 90g

Protein: 50g

Salt: 6g

On a packet label the Reference Intake (RI) value gives you an idea of how much that product contributes to your daily intake of calorie, fat, sugar and salt it’s also worth looking at this to give a guide as to how ‘big’ a meal this might be versus how big your portion size might be.

Food manufacturers are being encouraged to show consumers how much fat, sugars and salt is in their product as a percentage of the reference intake for that nutrient. Percentage reference intakes (%RIs) can be given:

• by weight (per 100g)

• by volume (per 100ml)

• and/or by portion

As you can see there’s a lot more to food labelling than meets the eye. Knowing how to understand what’s been put into food products and what that means to your health both now and in the future is very important indeed.